Fighting for Justice

The cost of a broken finance world

In 2019, 5 million people across the UK were identified as being at risk of being targeted for their pensions, equating to 42% of pension savers.

The stakes are high: in 2018 victims of pension fraud reported they have lost an average of £82,000 each.

The Financial Conduct Authority warns cold-calls, exotic investments and early access to cash are among the most persuasive tactics used by rogues.

Those who consider themselves financially savvy are just as likely to be ripped off.

Glossary

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) - the regulator in charge of supervising regulated financial services firms

Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) - pays out on behalf of regulated firms that have failed. Funded by the industry, its compensation is capped at £85,000 per claim (£50,000 before April 2019)

Financial Ombudsman Service - dispute body that can direct regulated firms to award up to £350,000 in compensation on claims brought by their customers

Unregulated investment - often high-risk investment that does not fall under the auspices of the regulator and is not protected by the regulatory dispute bodies

Regulated investment - an investment authorised by the financial regulator. Clients are eligible for recourse from the regulatory dispute bodies

Scam - a dishonest scheme, a fraud

Rip-off - not legally a scam, a high risk investment mis-sold as low risk

Pension scams and rip-offs have flourished since the government allowed people to access their pensions freely under pension freedom rules introduced in 2015. Under the rules anyone from the age of 55 can ask their pension scheme to release their funds subject to tax charges. To date £33bn has been withdrawn from pensions under the rules.

But while access to pensions was eased, consumer protections remained largely the same, leaving people vulnerable and exposed to scammers and other bad actors out to rip them off. These actors typically persuade them to invest their money into high risk unregulated investments, paying large sums of commission to the salesmen. By the time it transpires that the pension is lost, the rogues and their facilitators have often left the market, leaving consumers and the regulatory bodies to pick up the pieces.

In a hearing in March 2020 the head of the regulator, Andrew Bailey, told MPs he thought the pension freedoms had been introduced too quickly and the regulatory system has been in a 'catch up process' since.

1. Victims are targeted via regulated channels

High risk unregulated investments fall outside of the FCA's remit. But their providers can only gain access to a person's pension if they work with regulated financial advisers. This process culminates in a mis-sold investment or an outright scam, depending on the intention of the players involved. These constructs are difficult for the regulators to spot and often it is up to whistleblowers to expose them. By the time the rip-off is exposed the rogues have often disappeared.

Once the investment is complete investors are often re-targeted by regulated claims management companies, which offer help with arranging compensation payments from the FSCS. Whereas the claims process is free for people to use, these firms typically charge a hefty fee of 30% or more. The FCA last year stopped at least one such firm on suspicion that it was colluding with the original seller of the investment.

The whistleblower.

Leigh Hardy has made it her vocation to expose pension scams and rip-offs involving hundreds of UK pensioners since quitting her job at a pension firm three years ago. In her position she became aware of a concerted effort among some providers to siphon millions of pounds of pension money into unregulated schemes. This increased exponentially following a court case in 2016, which ruled pension schemes could not refuse a member's transfer request even if concerns about the possibility of a pension scam exist.

Leigh has collected evidence that firms are targeting people at both ends of the investment. Joining up the dots of directorships listed on Companies House for months, she sketched out a map of connected companies, both regulated and unregulated, on her living room wall. Eventually this became so big she had it painted over.

Leigh believes scammers and greedy rogues are exploiting shadow areas between the regulated and unregulated space.

I believe the FCA looks after what's in its remit, the police look after what's in their remit, and one of the biggest failures across the board is that none of the regulatory bodies, the Fos, FSCS and FCA, are interested in the unregulated. Everybody just wants to stick to what they do. But crime is getting more complex and the unregulated play such a massive part. We've got introducers, other unregulated businesses that siphon money, some unregulated firms in the chain are not even financial services firms.

The unwitting target.

One investor who has been targeted repeatedly is Dennis Holmes. He was cold-called with an offer to help him bring a PPI claim. Upon agreeing he became the target of an offshore property scheme eyeing up his pension.

At the time PPI was quite a thing and as I am not up to doing a claim myself I accepted and they came round to chat about PPI. They then asked about my pension and I explained I didn’t really want a pension review as the RAC looked after it and my Sipp was doing ok when I received my annual statements but they insisted that they had to do a pension review as part of my PPI claim."

The scheme arranged for a regulated financial adviser to 'help' Dennis transfer £33,000 of pension money into the unregulated investment. He was assured he was getting independent financial advice and the pension would be administered by a well-known reputable company. He never saw his adviser face to face. But his details were passed on to yet another company that got in touch after his investment showed signs of failing.

I have been contacted by another company saying they can help me to reclaim my mis-sold investment only to fInd out that they have directors linked to the exact people who sold me into [the scheme] in the first place.

Following the investment Dennis left his home in Hertfordshire for a new life in rural Lincolnshire as he no longer wanted to be surrounded by people working in finance.

When I say I have little faith and trust in anybody working in the financial industry you can see why. If I had anything to invest I would rather invest it under my pillow than trust anybody in that industry, which is a shame because I’m sure there are some good people working in finance and pensions.

2. Lives take a turn

Pension scams are costing savers an estimated £4bn a year. Analysis from the regulator has found 22 years of pension savings could be gone in just 24 hours as savers are trigger happy when it comes to making decisions about pension offers, often after being cold-called.

The FCA warns investors are often lured in with promises of high investment returns but this is not always the case. Increasingly they are offered help with consolidating their pensions and the ability to pass the funds to their children after they die. The aim is to reassure people that they and their family will be ok if they make the investment. The rogues know how to exploit people's general lack of knowledge when it comes to pensions, as under pension freedom rules any pension can be passed to descendants upon death.

Once it becomes apparent that their pension is lost investors' lives take a dramatic turn. The regulated salespeople have often left the industry and the unregulated investment company keeps them at bay with promises of future returns that typically don't materialise. All the while victims are being charged fees for the UK-based pension product through which they invested, and which can't be cancelled as long as the investment is held within it, valueless or not.

Fighting for compensation can be a cumbersome process, often adding months, sometimes years, of uncertainty to people's lives. As many pension investors are targeted at age 55, when they gain access to their pension funds under pension freedom rules, by the time they realise their predicament they have approached pensionable age, leaving their retirement at the mercy of the rogues.

The trusting target.

Elaine Jenkins's husband, Steve, was cold-called by a representative of an offshore hotel development company in 2012, who told him he could help him consolidate all his pensions into one £120,000 pot and put it in a 'safe' investment. This would yield enough for his and Elaine's retirement while allowing him to pass the money to their children should anything happen to him.

I remember the adviser sat in my kitchen telling us what a brilliant investment it was and how he wished he had the money to make an investment. I was so convinced we'd done the right thing I was on the verge of asking him to buy another apartment with another small pension. But he never pursued it. That was because it wasn't a big enough pot of money.

When the investment did not return dividends as promised three years later, the pair realised they had made a mistake. A separate financial adviser told them they had invested in a high risk unregulated investment.

We were both shocked and felt sick. My husband was very worried about what he’d done with his pensions and often said he felt stupid and let me down and had possibly jeopardised the future we had planned together.

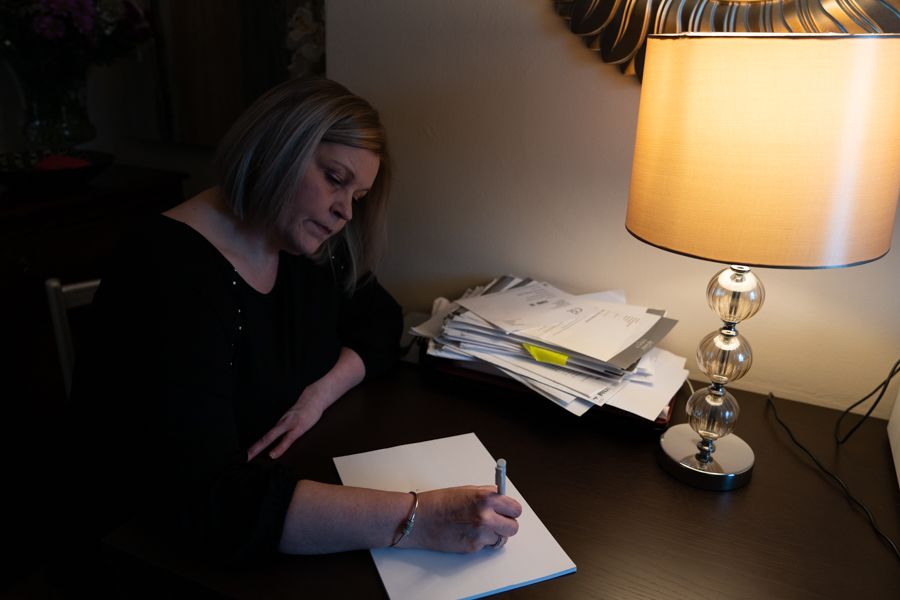

Steve died suddenly in August 2017. While dealing with his death Elaine notified the offshore company that she wanted to sell her investment. She was given several assurances but to date has not seen the money returned. Elaine also pursued the regulatory channels, and after a year of chasing was awarded £50,000 in compensation by the FSCS in September 2018, leaving her with an overall loss of £40,000.

I can't estimate the hours it's taken me and the worry as well. I can remember from June to September just being on the phone chasing the pension company, chasing the FSCS and chasing the management company to get information. When someone dies like Steve did it is a lot to get your head round and on top of that I had all of this to deal with. I'm fighting for the injustice. Steve died thinking he'd let us down and he hadn't, he'd been scammed.

Elaine wants policymakers to do more to protect vulnerable people from being ripped off.

There needs to be an alert system when people are trying to transfer out of their pensions, that someone independent goes in and says 'have you thought about this'. We just transferred our money out and there was no one to stop us. We were told we were getting independent advice and no one said 'stop, don’t do this'.

3. The safety net is tearing

The safety net for consumers lies in the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, which pays out on claims against regulated firms and products that have failed. But it has a limit of £85,000 per investment claim (£50,000 before April 2019), so people who lost more than that still suffer an overall loss.

Since it began in 2001, the FSCS has helped more than 4 million people, paying out more than £26bn in compensation. But the system is buckling under its own weight. The free to use scheme is funded by the financial services industry under a 'good guys pay' principle. This means firms that are still operating are having to pay out to clients of those that have failed (or wilfully gone out of business).

The contentious funding issue has plagued the industry for years against a backdrop of rising pension claims. Some financial firms have seen the cost on them increase by 400% year-on-year. The issue reached boiling point in early 2020 when a concerted effort to lobby for a radical overhaul of the system began.

The helpers.

Chief executive Caroline Rainbird and chairman Marshall Bailey are keen to make the system work for consumer and the industry, highlighting consumer trust and confidence as key towards achieving this aim. Recognising the vulnerability in its customers the scheme says it has stepped up its focus on empathy in its claims handling. But cases are increasingly complex and they need to be assessed thoroughly before any decision to compensate victims with the industry's money can be made.

At least 80% of our customers are what we would call vulnerable. With some claims they are complicated, we need to assess them, we need to make sure we have the right amount of evidence and we will help people with that. What we can do is manage expectations and commit to the deadlines we do give on communicating to those investors.

Ms Rainbird says the fee increase for the industry was regrettable but had been necessary to crack down on rogue firms and compensate consumers stung by pension-related fraud.

Behind all these complex terms and these large numbers and all sorts of things is a person who is vulnerable and wild, upset, frightened, angry and just generally not in a good place and none of us should lose track of that. We see each and every day stories, letters from people. We should never as an industry forget as we go about doing our business that these are people whose futures have been fundamentally changed.

4. Bad actors game the system

Phoenix - in ancient stories, an imaginary bird that set fire to itself every 500 years and was born again, rising from its ashes.

Not all advisers that have mis-sold an investment disappear forever. A growing phenomenon in the financial services industry is a practice called 'phoenixing', whereby directors of advice firms concerned about looming complaints against them shut up shop and start a new firm, taking with them clients and the business's assets but not its debts. Any claims falling on the defunct firm are then rerouted to the FSCS.

In 2019 the regulators formed a taskforce to clamp down on adviser phoenixing. By the end of the year the FSCS had identified 136 potential cases that it passed on to the regulator. At least seven advisers had been blocked from reauthorising by January.

The knowledgeable target.

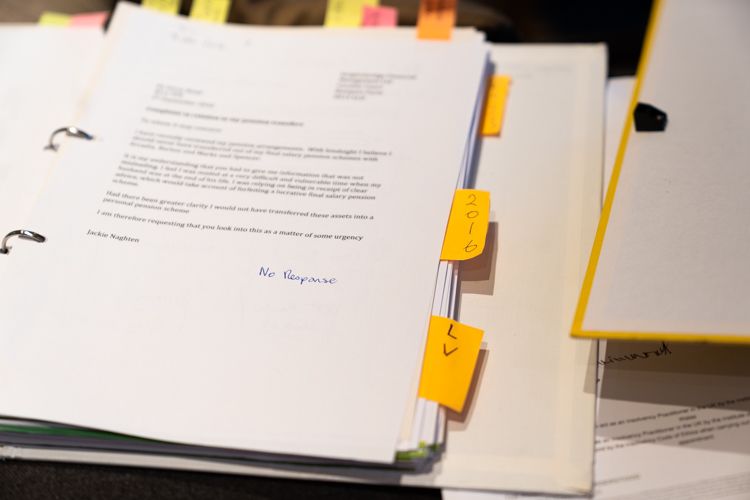

Jackie Naghten invested parts of her pension in a recycling scheme on the Isle of Man on advice from her regulated financial adviser. After the investment failed the adviser phoenixed, leaving her with an estimated loss of £470,000, of which she got £50,000 back from the FSCS. The adviser is back in business, advising new (and old) clients on where to invest their cash and pensions.

A successful business woman and former executive at a large high street retail chain Jackie is no stranger to finance. She was advised to transfer out of her pension during a time of extreme vulnerability and stress as her husband had entered the final stages of his life following prolonged illness. Jackie trusted her adviser, thinking she would be protected by the regulatory bodies if anything went wrong. She maintains she was never told the investment she had made was unregulated and high risk.

When filing a claim for bad advice, Jackie realised she could not claim on the adviser's insurance as his firm was no longer in business. She was never told her adviser had started a new business until she read about it in a newspaper article. Shocked by the news she took it upon herself to find out what had happened and to seek justice.

I spent probably three months solidly investigating and putting the whole story together. You really immerse yourself in it and you understand all the nuances and all the difficulties around it and then it completely consumes your life and you are a bit dysfunctional almost. It's a hugely time consuming exercise. I have a certain personality and resilience that makes it possible for me to do this but not everybody is like that. I think a lot of people just want it to go away and bury their heads, they feel ashamed, they don't understand it, they haven't got the time, they don't understand how it's been allowed to happen, how that person can get away with it.

Jackie says the financial system is too complicated for people to navigate. And trying to make sense of it can be a stressful and disheartening experience.

My message to the regulatory bodies is it needs to be much more consumer friendly, there needs to be greater clarity for customers understanding what they are getting themselves into. And there also needs to be a real look at the process IFAs engage in because a lot of them pretend to be independent [ but really] it is just Joe Blow coming to nick your money.

5. The policing bodies play catch up

The regulators, government and police are seeking to clamp down on bad actors and outright scammers with a series of defence mechanisms.

In 2012 they set up taskforce Project Bloom to respond strategically to the rise of pension scams. This work led to a cold-calling ban on pensions, stricter HMRC checks on the registration of suspected scams, and interventions on pension schemes suspected of being used by scammers. The taskforce was instrumental in winding up a number of rogue companies through the courts and disqualifying directors connected to pension schemes, clawing back millions of pounds of pension money for hundreds of victims.

Recognising that consumer education is key to beating scams and rip-offs, in 2014 the FCA and the Pensions Regulator launched the 'ScamSmart' campaign, an information campaign across TV, radio and online. Last year the campaign claims to have educated 180,000 people about the signs of a scam.

To tackle bad actors within the regulated industry, such as phoenixes, a partnership between the FCA and other regulatory bodies was launched in 2019. The group seeks to spot rogues through data sharing and analytics and wants to use machine learning in future. The taskforce identified 136 potential phoenixes last year and so far at least seven advisers have been stopped from reauthorising.

The regulator.

We're urging anyone who is thinking about transferring their pension to check who they are dealing with and only use firms authorised by the FCA. If you are ever in doubt about a pension offer, visit the ScamSmart website.

The police.

Education is the most important tactic in stopping fraud. Once we’re made aware of a fraud, steps are quickly taken to identify who is involved and take control of any assets from the scam so what is left can be returned to the victims. Unfortunately, victims often don’t report they have fallen victim to a scam in time to recover any of the assets from the criminal. This is why it’s so important that anyone who suspects they might be a victim, to contact Action Fraud immediately.

The policy maker.

We know that cold-calling is the pension scammers’ main tactic, which is why we’ve made them illegal. If you receive an unwanted call from an unknown caller about your pension, get as much information you can and report it to the Information Commissioner’s Office. [We] urge all savers to seek independent advice if you’re thinking about making an important financial decision.

The government and regulators have stepped up their game to crack down on scammers and others out to rip people off. But they rely on the regulated entities to play gatekeepers and the consumers themselves to safeguard their money.

Experience has shown by the time the regulators are in a position to act it's often too late.

By the time the sun rises the rogues have long gone.